Lavvu and Goahti

Sámi (Sápmi) culture, whose ancestors are a Uralic people from the Volga region of present-day Russia, are now indigenous to northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula within the Murmansk Oblast of Russia. There is no official geographic definition for the boundaries of Sámi. They are traditionally semi-nomadic fishers, trappers, and herders of sheep and reindeer. During the Bronze Age (c. 3200–600 BCE), Sámi people migrated into the coast of Norway (Finnmark) and the Kola Peninsula of northwest Russia. They do not refer to themselves as "Lapplanders".

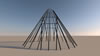

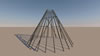

Sámi traditional temporary dwelling architecture is similar to the Native American tipi form (see pages ). Both dwelling types allow for a migratory nomadic lifeway. The fabric covered tipi looks very similar to a Sami lavvu, but often constructed slightly larger. The wisdom of both structures lies in their ratios of minimum exposed surface areas (for heat loss) to internal air volume ratios. The lavvu/goahti has an inherent structural stability resulting from its ubiquitous integral structural triangulation. There is no center pole needed to support this structure. The self-weight of the sod covered goahti makes staking-down unnecessary.

There can be three types of covering for a Sami lavvu/goahti hut or tent: fabric, peat moss or timber. Until the mid-19th century when inexpensive manufactured British textiles were made available to the Sami, Reindeer hides had been used as a cover.

Lavvus can be very large with with enough room for dozens of people and housing large families. Located in the middle of the lavvu interior is a fireplace used for heating and to keep mosquitoes away. The smoke escapes through the smoke hole in the top, usually left open, and to prevent smoke from building up inside, proper air circulation is maintained by open vents open along the lavvu base, or leaving the door slightly open.

The building stages of a Sami arch-beamed goahti (turf home): First an inner framework of two sets of curved wooden beams, are erected and braced with tree dforks. The curved trees used for these grow on hillsides. This structure of hyperbolic arches sits on stones with the final weight of the turf and its profile providing stability. The frame is pegged together with a wood ridge pole without the use of nails. Round wood poles are laid against the frame, pegged, and covered with overlapping sheets of birch bark, which are kept in place by the layers of turf stacked against the sloping walls.

The goahti floor was divided into nine areas, marked by logs or stones. On both sides of the door were logs that defined a path to the central fire place. There were also two wooden logs on the floor between the fire place to the back wall, which is the spiritual space in the home. The areas on either side of the fire place could be divided into several sections where people worked, ate, and slept.

Elevation is the range between sea level and 400 meters (1300 feet) above sea level.

Construction

Sources of data for CG models:

1. Emmons (Risten), Rebecca, 2004; An Investigation of Sami Building Structures.

http://www.utexas.edu/courses/sami/dieda/anthro/architecture.htm

2. Natural Homes, (eds.), 2020; The Sami (indigenous skandinavian) Gamme or Goahti (turf home)

http://naturalhomes.org/turfhouse.htm

3. RGDN (eds), 2016; Lake Seydozero. Traces of an ancient civilization

https://rgdn.info/en/seydozero._sledy_drevney_civilizacii

4. Muus, Nathan, and Westcott, David, 1997. "Building a Lavvu", Bulletin of Primitive Technology, Fall, 1997 , No.14. p.21-22.

5. https://web.archive.org/web/20100617162422/http://home.online.no/~sven-ok/Lavvo.htm.

-NewTexZyy-_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZxx_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZzz-_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZZ-_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZ3-_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZ2-_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZinterior1_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZInterior1-_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZInterior3-_tmb.jpg)

-NewTexZMontage3Flat-_tmb.jpg)