Colorado Solar Hogan Demonstration

College of Environmental Design, University of Colorado/Boulder, 1987-1990

This Project is a collaboration with Dr. Charles Cambridge

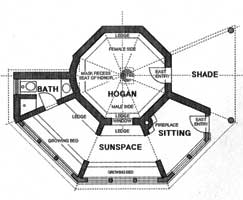

Three solar hogans in a meadow next to the Univerisity President' residence and floor plan for the "middle-way hogan".

Photograph: Ginny Grimm for Native Peoples Magazine

Solar Hogans, Houses of the Future?

By Hassell G. Bradley

(This story originally appeared in Native Peoples, Volume 3, Number 3, Spring 1990, published by Media Concepts Group, Inc. in affiliation to: The Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ; The Iroquois Indian Museum, Schoharie, New York; The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, New York, New York; and the Southwest Museum, Los Angeles, California.)

Legend says that the first hogan, the traditional circular Navajo dwelling, was built for Changing Woman, a deity. Her hogan was connected to heaven by a rainbow that filled the sky with arcs of color.

Charlie Cambridge, Navajo archaeologist and a doctoral candidate in anthropology at the University of Colorado in Boulder, admits that no one will ever discover where in the Southwest the first hogan was built. This resolute, solidly-built man in his mid-forties is, however, certain of two things: the circular hogan possesses spiritual power, and it is particularly adaptable to solar technology and modern living.

For much of his life, Cambridge has dreamed of developing a solar hogan to make life easier for Navajos who want to live in their old age on the reservation, which requires coping with harsh weather and often no electricity or running water.

He persisted in his pursuit of this vision until three demonstration hogans using different types of solar technology were completed on the University of Colorado campus last year. Constructed between patches of bull nettle and cattalils and a grove of scraggly cottonwood trees, the hogans have been blessed by a medicine man. Cambridge arranged for George Bluehorse, a Shiprock, New Mexico medicine man, to conduct a Blessingway last October.

"A Blessingway," Cambridge explained, "is a Navajo chant that created harmony between a hogan and the people who live in it."

Cambridge, who wears his hair long and straight, rubbed his hand across his broad face and looked thoughtful. "Many of the old Navajos want to live out the rest of their lives on the reservation. But they are often relocated out of their hogans into the rectangular box houses that HUD officials like." He shook his head in dismay. "Very often these box houses block a neighbor's sacred northern view."

Regardless of their age, Navajos who are moved into rectangular houses often experience a sense of profound loss, he said.

Why is the hogan so essential for Navajo contentment? Does Changing Woman's rainbow still exist in the Navajo psyche? Could living in hogan-like homes bring benefits to non-Indians?

"The circular hogan with its east-facing door and its earthen floor is constructed to encourage harmony, just as the spiritual beings first instructed," Cambridge explained. "The round hogan is female, and there are certain places you must sit if you are male or female, if you are a visitor or a medicine man. Navajo society is reflected in a hogan's design."

Born in Farmington, New Mexico, Cambridge was the first member of his family to attend public school. In the late 1950's, after he entered Durango High School, he was elected president of the school's science club.

"When I was a senior," Cambridge said, "A Bureau of Indian Affairs official came by the school and asked to see some Indian kids. He talked to me and suggested I study baking at Haskell Institute."

While digging through his briefcase looking for an application for Haskell, the BIA official came across a math and science camp form. The camp was later canceled, but Haskell officials assumed Cambridge was interested in post-secondary education. They gave his name to the Navajo tribal scholarship office, which sent along an IQ test.

Cambridge's high score resulted in a scholarship and he enrolled at the University of Colorado.

"One night", he recalled, "I was walking through a university building, and I heard Indian drumming. It was bizarre. I was the only Indian student at the University of Colorado. I followed the sound around the corner and discovered a meeting of the anthropology club. My interest in anthropology began that night." As far as Cambridge knows, he is the only Navajo with credentials in both anthropology and archaeology.

How does Cambridge reconcile his scientific training with his traditional belief that dead spirits are dangerous and can bring sickness, trouble and even death to the living?

"When I dig," he said, "I say to the dead ones, 'You have the power to make me ill or to cause my death. But there are reasons to make me ill or to cause my death. But there are reasons I must did here.' In all the years I have been digging on the reservation, I have never had any trouble."

Cambridge's scientific and spiritual views go hand in hand with his work on the solar hogans. However, his dream of developing an energy self-sufficient hogan became reality when he met Dennis Holloway, a tall, slim, Harvard-trained architect and faculty member at the University of Colorado's College of Environmental Design. The two were introduced by a mutual friend six years ago at the Trident Cafe in Boulder.

He and Holloway started talking, Cambridge recalled. "Before long, I was sketching out my idea for a solar hogan on a Trident napkin."

From Cambridge's sketches, Holloway proceeded with a thorough analysis. The result was plans for three hogans, ranging from simple to complex. The men had as their goal solar structures to benefit reservation Navajos as well as urban residents who want to build energy self-sufficient homes.

It took time for Holloway and Cambridge to persuade university officials that their idea was sound. Permission was finally obtained to build three solar hogans on the campus. Twice, building supplies were stolen, and bureaucratic delays slowed things.

But in the end, the Colorado Solar Hogan Project succeeded, thanks to a combination of Cambridge's determination, Holloway's expertise, and insight on the part of the Colorado Office of Energy Conservation and the University of Colorado. Funding came from the state of Colorado and from the university. The university also provided supplies; labor came from students and community volunteers. (Holloway dubbed these volunteers the "hogans' heros.") Work on the solar hogans stretched over a two-year period.

As is often the case with new ideas, they surface in more than one place at the same time. In late October, 1989, the month the hogans were completed and a Blessingway was held for them, the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe coincidentally held a three-day symposium, "Cosmos, Man, and Nature: Native American Perspectives on Architecture."

Susan McGreevy, Vice President of the Wheelwright Museum's Board of Directors, said, "Native American structures symbolize how human beings fit into the universe. For example, a Navajo hogan includes many symbolic aspects, such as the four cardinal directions and the east-facing door. Most significantly, the instructions on how to build a hogan were given to the Navajos by spiritual beings, according to tribal origin myths."

Today, three culturally-relevant and energy-self-sufficient circular hogans have been erected at the base of Boulder's foothills near the intersection of Highway 36 and Baseline Road. One is a simple, traditional-style hogan; another--called transitional--incorporates some modern energy-conservation ideas; the third is a dramatic contemporary hogan with many amenities. Often, Cambridge has seen motorists glance at the hogans, then swerve their vehicles and come to a stop for a closer look.

The Colorado Solar Hogan Project has produced a prototype for a dwelling that is a traditional hogan attached to compatible, modern circular dwelling that demonstrates how Navajo culture can influence new forms of housing. The simple, traditional round hogan is 16 feet in diameter with a domed, cribbed ceiling of peeled logs which form a pattern of lines stretching to infinity at the smokehole. In summer, weeds flourish on the roof, reaching for the sun.

Holloway's design for the "transitional" hogan utilizes an encircling flagstone wall with casement windows built on the east and south and west sides. The added wall creates a protected space where, Holloway and Cambridge like to imagine, a Navajo grandmother might sit and weave or tell stories to her grandchildren.

Framing on three south-facing exterior walls (of the "traditional" hogan) holds a fiberglass glazing material developed with the help of Arnold Valdez of Ghost Ranch, New Mexico. The glazed walls are heated by the sun and become the primary heat sources, reducing dependency upon woodburning.

Southwest of the transitional hogan stands a red-sided structure built into the hillside. The strange looking hogan has a lower living level that fans out into 1600 square feet of living space, including a kitchen and a bathroom.

Insulated glass windows angle at 50 degrees on the southern walls to receive the sun's rays in winter and to bounce them off in the summer.

With its cribbed ceiling and east-facing door, Holloway's creation is undeniably hogan-like. Heat and electricity are produced by combining active and passive technologies. Outside, photo voltaic cells track the sun, and closed-system solar collectors heat water in a 120-gallon tank. Inside, vegetables can be grown in flower beds.

Since this modern hogan was designed for conditions that currently exist on the reservation, water from a reservoir is pressurized with a solar-powered pump for bathroom and kitchen use. A waterless toilet has been installed, and back-up heaters, a stove and a refrigerator operate on propane.

"We have projected several variations that come within HUD design-and-cost guidelines ($70,000 or under)," Holloway said. "The result will be more satisfying to Navajos and a better use of tax dollars."

Immediately above the lower living level stands a traditional hogan to be used for the Blessingway ceremony. Its door can only be entered from the outside, terraced walk.

"The cribbed ceiling gives the harmonious sensation of the sacred circle," Holloway pointed out.

The week before the Blessingway was to be held, Holloway, Cambridge and their student and volunteer work crews raced to finish the hogans in time for the ceremony.

"I went down to Stapleton International Airport in Denver to pick up the medicine man," Cambridge recalled. "His plane was three hours late, and I didn't know if we could get back to Boulder in time. A lot of dignitaries were going to be on hand to make speeches."

Finally, George Bluehorse's plane landed; within minutes, he and Cambridge were in a taxi racing to Boulder and the Blessingway. Bluehorse is a humble man with a wiry build and a quick smile.

"While we were in the taxi," Cambridge said, "the medicine man told me a story that his father told him. He said, 'The twin gods of war went to the sun to accuse him of being their father. The sun lived in a solar house. The sun told the twins that in the future, all the Navajo people would live in solar houses and that the young people would make this happen.'"

At last, the taxi arrived on the campus. The crowd gathered around Bluehorse and Cambridge. The Blessingway would soon happen.

Bluehorse, Cambridge, Holloway, local dignitaries and a few Navajo students went immediately to the little, traditional hogan. Singing hogan-blessing chants, Bluehorse led the group inside and shut the door.

Outside, a crowd gathered around. Before long, pungent smoke spiraled out of the smokehole. "Look!" a man cried, pointing up to the sky. A thin cirrus cloud had passed across the sun. There, circling the cloud's leading edge, were three rainbows. The power of the circle was in the sky for everyone to see.

Finally, the hogan door opened, and the medicine man and the celebrants came outside and sat down on the green carpet spread out on the ground.

"This ceremony is usually conducted only for family members," George Bluehorse told the crowd. "But we are all one huge family today. We will bless the other two hogans here so everyone can watch. The purpose of the ceremony is to thank Mother Earth, who provides the water. We use corn pollen and cornmeal to bless these hogans. The hogans are female."

Charlie Cambridge knelt, sage in hand, beside his sister, Debbie Raymond, who fashioned a base of white sand on the green carpet and then layed on it a fire stick of white wood.

Bluehorse turned back to the crown. His turquoise necklace hung to his waist, and his silver belt glinted in the sun. "I feel I'm very honored to conduct this ceremony for the hogan. The old people prophesied that someday they could see a hogan like this solar hogan."

Chanting, the medicine man adjusted the eagle feathers in the basket and sprinkled corn pollen. Responding to his chant, a spectator in a gray shirt rocked back and forth in rhythm.

After the ceremony, Cambridge confided that he had been in a state of controlled panic much of the day. "But now," he said, "I have a sense that a great burden has been lifted from my shoulders. There has been massive public approval for what we have done here.

"This hogan is causing a tremendous stir among architects. But more important, this will change the Navajo Nation.

"The people who live on the reservation see the energy companies taking away Navajo natural resources. Someday, our people will have to pay a lot of money, maybe $250 a month, for electricity. But with solar hogans, they can be self-sufficient."

Peterson Zah, former chairman of the Navajo Nation said, "I was in Boulder the fall of 1089 to look at the solar hogans. I was very impressed. They (Cambridge and Holloway) have retained the layout of the traditional structure, and they are also allowing the solar rays to heat the hogans. This is very practical for individual Navajos who want to build these hogans for themselves."

Leonard Watchman, executive administrator of the Navajo Housing Authority, said, "We saw the solar hogan a year ago. I personally think it is a worthwhile project, especially for remote areas. The Navajo Housing Authority is interested in supporting a similar project, but our problem is dealing with HUD guidelines."

"People on the reservation are beginning to get the idea, because they have heard about these hogans," Bluehorse said. "They are getting solar energy into their hogans any way they can."

Bluehorse said when Cambridge asked him to do the Blessingway, he went to his father and asked if he should agree to conduct it. "He told me I should go ahead, and told me the story of the sun houses. I went to the sweat lodge with two friends, and we prayed about it. The important thing was to reach the young people. We did that."

Since the Blessingway was performed on October 6, 1989, Holloway and Cambridge have been involved in negotiations independent of HUD in the Ramah and Chinle areas on the reservation to build solar hogans. A large mining company has invited them to submit a proposal for a demonstration solar hogan. The two men are hopeful that their efforts really will benefit Navajo lives.

George Bluehorse summed up the general feeling about the hogans: "The Great Creator granted these special hogans. During the last song I did inside the hogan, I felt something special, spiritually. The sun went along a trail of a special prayer. Beautiful things were happening."

Holloway and Cambridge did not know about the rainbow in the sky over the hogans until later. Now they cannot forget what happened.

After all, Cambridge pointed out, the first hogan was built for Changing Woman. And everyone knows that a rainbow connected her hogan to heaven.

Above: Dine Medicine man, George Blue Horse (with headband) conducts a Blessingway ceremony for hogans as Charlie Cambridge and his sister, Debbie Raymond, look on. Photograph: Ginny Grimm for Native Peoples Magazine.

Dr. Charles Cambridge says this about the Meaning of the Navaho Hogan:

|

|

|---|---|

A Male Hogan, door facing East. |

A Female Hogan, door facing East.. |

"Hogan" is a Navaho word translating roughly into "home place" that has meanings of shelter, house and a place for family activities. The hogan is the traditional housing of the Navaho people, who are a tribe of American Indians located in the United States' Southwest region. The hogan is a circular and dome house. In Navaho mythology, the first hogan was built by the Gods and Spirits for a newly born Navaho goddess, Changing Women. Because of this sacred beginning, the Navaho hogan is viewed as sacred, andtherefore must be constructed in a certain manner. When the hogan construction is completed and before occupation, a Blessing Way ceremony must be conducted to ensure good fortune for the hogan and the family who will occupy the new hogan.

Normally, the hogans are one-room dwellings and the single room is never subdivided. Hogans are ordinarily circular and may have a polygonal shape. Octagons are the usual floor plans. The traditional hogan is never rectangular in its shape. The hogan is usually 16 feet in diameter with a domed, cribbed ceiling of peeled logs with a smoke hole at the top. The perimeter walls are usually 5 1/2 to 6 feet high. On an average, the interior height of the dome will reach 10 feet. The floor level of old style hogans was about 24 inches below ground leve. This allowed a natural bench to be created inside the hogan. The hogan walls are constructed of overlapping and mud- covered logs or sandstone. The dome roof is a cribbed ceiling that is made of overlapping mud-covered logs. The dome form is reflective of the sacred sky. This hogan form represents the female. Male hogans are short cone shape structures. The female form is the typical structure.

The circular hogan has an east-facing door and earthen floor. On the first day of construction, the hogan's single doorway is centrally oriented toward the raising morning sun. The central point of the doorway is marked where the first rays of the morning's of dawn. This blesses the hogan with the sun's first rays. The traditional doorway was covered with animal hides or later by woven rug like covering. Contemporary hogans use wooden materials with hinges for the doors. Traditional, hogans are windowless. Light enters through the doorway and smoke hole. Contemporary hogans may allow a single

window that may be located on the south and west walls. The north wall may never have a window because the dead reside in the north. The traditional hogan's fire hearth is on the dirt floor with the smoke hole that is 1-1/12 feet east of the center of the dome roof. The hearth is on the flat surface of the floor with a large flat stone set at one of the cardinal directions of the fire. Contemporary hogans have replaced the hearth with small wood burning stoves.

Within the hogan, spaces are culturally or religiously defined. Males sit on the North side while females must sit on the South. Visitors or medicine people are required to sit on the West and from this position they face the East. So, a hogan has representation of the four cardinal directions with an east-facing door. The hogan is a blend of the harmony of the Navaho and their Spiritual Universe. Importantly, the hogan represents the Navaho cosmos and is the center of their religious being. The hogan's form and technique of construction have remained relatively unchanged for centuries.

An experiment in blending traditional architectural design of the Navaho hogan with solar and appropriate technology was undertaken at the University of Colorado in Boulder, Colorado. The experiment includes the construction of three demonstration hogans using solar passive design and technology on the University's campus.

Published Reviews of Colorado Solar Hogan Project :

1. "The Solar Hogan Project", by Richard Simonelli in Winds of Change (A Magazine of American Indians), published by AISES, Boulder, Colorado, Spring 1989, pp. 32-38.

2. "Passive and Low Energy Architecture - Architecture and Technology: Environment-conscious Design in the 1990's - a World Survey" Process Architecture , Tokyo, Japan (English and Japanese), No. 98, pp. 138-139. (Solar Hogans are reviewed in this special issue.)

3. "Home Again, Ancient Navajo hogan goes high tech to preserve energy and a way of life", by Peter Caughey in Summit Magazine (CU Boulder), Fall 1989, pp. 2-5. Review of Mr. Holloway's design (in collaboration with Charles Cambridge, Anthropologist) for the Colorado Solar Hogan Demonstration.

4. "Solar Hogans, Houses of the Future?", By Hassell Bradley, in Native Peoples Magazine, Spring 1990, pp. 44-50. Review of Mr. Holloway's design (in collaboration with Charles Cambridge, Anthropologist) for the Colorado Solar Hogan Demonstration.

5. "Holloway Blends High-Tech with Tradition", in Portico Magazine (College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan), Volume 7 Number 2, Winter 1991, pp. 10-11. Review of Mr. Holloway's design (in collaboration with Charles Cambridge, Anthropologist) for the Colorado Solar Hogan Demonstration.

6. " 'Culturally relavant' campus housing adds a technological twist to a Navajo tradition". Los Angeles Times. February 26, 1990. page A 14.

7. "Colorado Solar Hogan Project", in California Indian Energy News (California Energy Extension Service, An Energy Management Action Program of the Office of Governor Pete Wilson), Vol. 2 No. 2, Spring, 1992, pp. 4-5. Review of Mr. Holloways work on the solarization of the traditional Navaho Hogan.

8. Renewables are Ready, People Creating Renewable Energy Solutions, by Nancy Cole and P.J. Skerrett, Union of Concerned Scientists , CHELSEA Green Publishing Co. 1995. Containts a review of Colorado Solar Hogan Demonstration.

9. Contemporary Native American Architecture, Cultural Regeneration and Creativity, by Carol Herselle Krinsky, Oxford University Press, London & New York, 1996. Contains reviews of the context and design process for the Colorado Solar Hogan Demonstrantion , and Poeh Culture Center and Museum, designed for Pojoaque Pueblo by Mr. Holloway.

10. "University of Colorado builds solar Navajo hogans", in Lakota Times, October 11, 1988 (page 6).

F i l m s , V i d e o , & O t h e r M e d i a :

1. The Colorado Solar Hogan Demonstration, (Prepared by The University of Colorado / Boulder, Office of Public Relations), 1989.

2. "The Colorado Solar Hogan Demonstration", a ten-minute segment on the independent Australian television science series, Beyond 2000. Satellite telecast in sixty countries.

3. "Solar Hogan Feature". National Public Radio. Nationally aired program, May 14, 1989.